Fall is here, and that makes us crave rich, hearty comfort foods and the earthy, rustic wines that complement them so well. While we believe in drinking whatever you like all year round, there is something that just feels so right about the pairing of robust stews, risottos, and roasted meats with wines brimming with aromatics that could easily be described as 'autumnal'--from fallen leaves to fragrant herbs to holiday baking spice. The regions of Burgundy, France and Piemonte, Italy are two producers of such wines--and they have more in common than meets the eye, as do their primary red wine grapes, Pinot Noir and Nebbiolo. To start with, an overview of the grapes themselves:

Both of these ancient varieties have complex family trees. Because they have been around for so long, many clones of each variety have developed over time, through the natural process of mutation. Pinot Noir, in particular, is an ancestor to an astounding number of grape varieties, including Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin Blanc, Merlot, Malbec, Syrah, and Viognier--to name a handful. Nebbiolo's resume is a little less impressive, due in part to the fact that the cultivation of much of its progeny, such as Vespolina and Freisa, has not spread much beyond their birthplace of Piemonte.

On the vine, Pinot Noir and Nebbiolo almost look like they could be related, although there is no genetic connection between the two varieties. Both grow in tight bunches in a lovely shade of bluish-purple, are late to bud during harvest, very susceptible to disease, and extremely finicky about where they like to be grown. They even prefer the same type of soil--those that are calcareous, meaning that they are partly or mostly composed of calcium carbonate. These chalky soils, high in lime content, allow these difficult-to-grow grapes to reach their fullest potential. To grow Pinot Noir or Nebbiolo on the most suitable vineyard sites is like commissioning the work of a talented yet temperamental artist--at times it can be frustrating or infuriating, but the end result is a masterpiece well worth the hassle. In ideal conditions, it is a widely held belief by wine lovers throughout the world that Pinot Noir and Nebbiolo produce the finest wines in their respective countries of France and Italy. Many would even say they are among the best in the world. In a good vintage, these grapes give highly expressive, hauntingly beautiful wines with excellent aging potential. In fact, while many of the best wines made from both Pinot Noir in Burgundy and Nebbiolo in Piemonte are ready to drink (and difficult to resist!) in their youth, given time to soften and mature they can often continue to improve up to a decade or even two. The patient oenophile will be rewarded handsomely with complex aromas and flavors: red cherry, raspberry, forest floor, truffle, game, and violets can be found in both, along with Nebbiolo's signature notes of tar and rose. Though the flavors can be quite similar, each wine provides a very different sensory experience. Pinot Noir tends to be soft and velvety, while Nebbiolo's surprising tannin and structure are masked by a light, pale appearance.

The growing regions of Burgundy and Piemonte themselves have much in common, as well. Both are highly fragmented, partially because there is great diversity in the terroir of each (and there are arguably no other red wine grapes more expressive of terroir than Pinot Noir and Nebbiolo). There is variance in soil composition, slope, sunlight exposure and more that makes each small pocket of land unique. This can make learning about these regions a bit overwhelming. This is further complicated by the fact that vineyard ownership in Burgundy is governed by the Napoleonic code: when a vigneron passes away, his land is divided equally between his surviving heirs, creating a system where some vineyard owners may posses only one row of vines. Many growers in both Burgundy and Piemonte tend to own parcels of vineyards in various districts within the broader appellation. Both regions have strict rules in place to ensure quality wine production. Pinot Noir is required to comprise 100% of Bourgogne AOC, while Nebbiolo is mandated to do the same for Barbaresco DOCG and Barolo DOCG, the highest quality wines produced in Piemonte.

Thanks to these venerable regions, we are able to enjoy an enriched autumn sensory experience. Let a Premier Cru Burgundy delight you with a whiff of damp fall leaves, or get inspiration for a hearty meal from the intoxicating truffle aroma of a great Barbaresco. Here are some wines will allow you to do just that, so you can see for yourself just how similar yet unique these two spectacular wine regions really are: 2011 Lucien Muzard & Fils Bourgogne Medium-bodied and eminently drinkable, this is Bourgogne AOC doing what it does best. Tart, juicy, and mineral with aromas of red cherry, violet, and fresh earth, this wine is velvety on the palate with bright flavors of cranberry and rhubarb. 2010 Domaine Camus-Bruchon & Fils Premier Cru Savigny-Narbantons With a Premier Cru Burgundy, things get a little more complex. Baking spice dominates the nose, particularly cardamom and anise, with an element of wet stone and forest floor. While red fruits like rhubarb and currant make an appearance here as well, the fruit is darker and more brooding than the Bourgogne. The beautiful, complex finish is seemingly endless. 2010 was a classic vintage in Burgundy, showcasing both the Pinot Noir grape and the regional terroir at their best. Camus-Bruchon's Narbantons comes from the Beaune side of Savigny and has a little more weight than his other Savigny wines, which makes this bottling so appealing right now. 2011 Produttori del Barbaresco Langhe Nebbiolo It's hard to find a better deal on Piemontese Nebbiolo than this one. Classic tar aromas and flavors are balanced by high-toned, lively notes of bright red cherries and raspberries and pleasant acidity. The tannins are much softer and more approachable here than in many otherwise comparable wines. This wine could technically be classified as Barbaresco, but since the grapes come from the youngest vines, the winery chooses to label it as Langhe Nebbiolo in order to preserve the excellent reputation of their top-tier wines. 2011 is a year in which the Nebbiolo fruit really sings, and this example from one of the region's top producers truly exemplifies the finesse for which Barbaresco is known. 2007 Sottimano Barbaresco 'Pajoré' Through consistent high quality, the Pajoré vineyard has rightfully earned its status as one of the most famous vineyards in the Langhe. This excellent example from Sottimano shows great complexity with elegant notes of violet, rose, tar, blueberry compote, clay, five-spice, anise, tobacco, and cedar. While it's drinking great now, this highly concentrated wine should continue to improve for years to come--if you can wait that long. The whites of these regions are excellent as well: 2011 Domaine Romain Collet Chablis 'Les Pargues' This is a great example of Chablis from a vintage that was more about elegance and purity than power and concentration. Light, refreshing, and mineral, this one is perfect for warm Bay Area autumn days with a hint of crispness in the air. 2012 Giovanni Almondo Roero Arneis 'Vigne Sparse' Made from 100% Arneis, this medium-bodied, aromatic wine is brimming with white flowers, lemon, and fresh green pears, and a chalky minerality reminiscent of Chablis. The Arneis grape is often planted near Nebbiolo vines, in order to distract birds with its pleasing perfume so that they refrain from snacking on the higher-market-valued Nebbiolo grapes. With one whiff of this wine, it's easy to understand that logic. |

Sunday, November 17, 2013

An Exploration of Burgundy and Piemonte

Labels:

Bourgogne,

Camus-Brouchon,

France,

Giovanni Almondo,

Italy,

Langhe Nebbiolo,

Muzard et Fils,

Pajore,

Piemonte,

Produttori del Barbaresco,

Roero Arneis,

Romain Collet,

Savigny-Narbantons,

Sottimano

The Stunning Pouilly-Fumé Wines of Domaine Dagueneau

Didier Dagueneau, maverick of the Loire Valley, produced some of the greatest Sauvignon Blancs the world has ever known. Unfortunately, his life and his career as a vigneron were finished far too soon, in a manner which, though devastating, wouldn't have been much a surprise to those who knew him. A perennial thrill-seeker and risk-taker, Didier, who also enjoyed professional motorcycle-racing and later, dog-sled racing, met his untimely end at the age of 52 when the ultralight plane he was piloting crashed shortly after landing in September of 2008. During his tenure at the helm of Domaine Dagueneau, Didier adopted a similarly unorthodox attitude in both the vineyard and the cellar.

The wines of the Pouilly-Fumé AOC are prized for their minerality and perfume, with a smoky aroma (hence the name 'Fumé', French for 'smoked') often making an appearance in the best examples, Dagueneau's not withstanding. This is largely owing to the presence of flint (which, combined with clay, is known locally as 'silex') in the region's famed limestone soils. These top-tier wines can age longer than your average Sauvignon Blanc--five to ten years for many, and even up to twenty for Dagueneau's finest bottlings.

Didier was not afraid to break the rules, and those who consume the wines of his domaine will be handsomely rewarded by his experiments. Low-yields were an established constant, but the boundaries of viticulture and viniculture were constantly pushed, from organic viticulture to natural fermentations to experimental barrels. Unlike most Loire Valley Sauvignon Blanc, Dagueneau's wines have always been raised in oak barrels, though the size, shapes, and proportions of new to neutral barrels has varied with both vintage and vineyard.

Didier may no longer be with us, but his children, Charlotte and Benjamin, have taken over the domaine and continue to produce stunning wines with clarity, precision, and freshness that wine critics agree would make their father proud. The most recent releases are no exception.

The 2010 Blanc Fumé de Pouilly, Dagueneau's "entry level" cuvée, is intended to be a very direct, pure, and typical example of Sauvignon Blanc from a typical Pouilly-Fumé vineyard. It truly is a spectacular example of what wines from this AOC should aspire to be--brimming with chalky minerality and racy citrus.

The 2011 Pur Sang, perhaps the Domaine's most popular cuvée, is bursting with aromas of citrus, quince, and fine minerals, with mouth-puckering acidity punctuating the intense and ethereal palate. The grapes come from chalky limestone soils that are almost entirely lacking in silex.

The 2011 Buisson Renard, grown on silex soil and formerly the most mineral of the Dagueneau cuvées, is tamed by oak ageing to form a rich, opulent wine held together by a firm, flinty backbone.

Finally, the 2011 Silex is the "Grand Cru" of Dagueneau's wines. Highly sought-after year after year, this wine can be slightly more austere than its contemporaries, due to lower clay content in the soil. This may not be the right wine to pop open tonight, but those who are patient enough to wait for this stunning wine to reach its peak will reap significant benefits.

Labels:

Blanc Fumé de Pouilly,

Buisson Renard,

Dagueneau,

Didier Dagueneau,

Domaine Dagueneau,

France,

French Wine,

Loire Valley,

Loire Wine,

Paul Marcus Wines,

Pouilly-Fumé,

Pur Sang,

Sauvignon Blanc,

Silex,

Wine

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Jurassic Wines: They're Not Just for Dinosaurs Anymore (New Arrivals from Jura!)

Tucked in between Burgundy and Switzerland, the Jura wine region has, until recently, somehow managed to remain off the radar of most American consumers. It's sort of understandable--this area tends to produce the favorites of wine geeks in search of something new and different. However, a bit of understanding can lead to appreciation by any wine drinker for these unique and often 'funky' wines.

Jura's unusually cool climate allows the production of refreshingly crisp whites with mouthwatering, tart acidity and ultra-pale reds that astonish with their unexpected complexity. Sparkling wines, known as Crémant du Jura, thrive here as well, taking advantage of high acidity levels in the grapes to make wines that are similar to Champagne--but a lot more affordable. Easily recognizable Chardonnay and Pinot Noir beckon the uninitiated with their familiarity, a gateway to the more obscure grapes of the region--Savignin (known elsewhere as Traminer), Poulsard, and Trousseau.

The most distinctive, and probably best-known wine style of Jura is Vin Jaune, or' yellow wine'. To make Vin Jaune, very ripe Savignin grapes must be harvested from low-yielding vines. They go through the usual white wine routine--conventional fermentation, secondary malolactic fermentation...seems pretty standard, at first. But here's where things get crazy--the wine is then transferred to old Burgundy barrels that are filled incompletely, and placed in an area that is well-ventilated and therefore subject to temperature fluctuations. This is basically the opposite of how a winemaker would want to store any other type of wine during the vinification process, but for Vin Jaune, this is how the magic happens. Owing to these unusual conditions, a thin layer of yeast (known as the voile) forms on top of the wine, similar to the flor in Sherry. Then the winemaker must sit patiently for at least six years, as the wine slowly oxidizes, protected by the voile from turning to vinegar. This patience is eventually rewarded with the resulting dry, aromatic, nutty wine--often with aromas and flavors of exotic spics such as turmeric, cardamom, and ginger, walnut, almond, apple, and sometimes honey, with a deep yellow-orange appearance. For best results, Vin Jaune should be allowed to breathe for a while before serving, and paired with its neighbor and natural ally, Comté cheese.

A thorough exploration of the wines of the Jura region would comprise a wide variety of flavors and styles. It's always nice to start off with some bubbles, and Domaine de Montbourgeau's Crémant du Jura is an excellent choice. This 100% Chardonnay sparkler is light, fresh, and bursting with racy citrus acidity, making for the perfect aperitif or a great bottle for brunch.

Jura's unusually cool climate allows the production of refreshingly crisp whites with mouthwatering, tart acidity and ultra-pale reds that astonish with their unexpected complexity. Sparkling wines, known as Crémant du Jura, thrive here as well, taking advantage of high acidity levels in the grapes to make wines that are similar to Champagne--but a lot more affordable. Easily recognizable Chardonnay and Pinot Noir beckon the uninitiated with their familiarity, a gateway to the more obscure grapes of the region--Savignin (known elsewhere as Traminer), Poulsard, and Trousseau.

The most distinctive, and probably best-known wine style of Jura is Vin Jaune, or' yellow wine'. To make Vin Jaune, very ripe Savignin grapes must be harvested from low-yielding vines. They go through the usual white wine routine--conventional fermentation, secondary malolactic fermentation...seems pretty standard, at first. But here's where things get crazy--the wine is then transferred to old Burgundy barrels that are filled incompletely, and placed in an area that is well-ventilated and therefore subject to temperature fluctuations. This is basically the opposite of how a winemaker would want to store any other type of wine during the vinification process, but for Vin Jaune, this is how the magic happens. Owing to these unusual conditions, a thin layer of yeast (known as the voile) forms on top of the wine, similar to the flor in Sherry. Then the winemaker must sit patiently for at least six years, as the wine slowly oxidizes, protected by the voile from turning to vinegar. This patience is eventually rewarded with the resulting dry, aromatic, nutty wine--often with aromas and flavors of exotic spics such as turmeric, cardamom, and ginger, walnut, almond, apple, and sometimes honey, with a deep yellow-orange appearance. For best results, Vin Jaune should be allowed to breathe for a while before serving, and paired with its neighbor and natural ally, Comté cheese.

A thorough exploration of the wines of the Jura region would comprise a wide variety of flavors and styles. It's always nice to start off with some bubbles, and Domaine de Montbourgeau's Crémant du Jura is an excellent choice. This 100% Chardonnay sparkler is light, fresh, and bursting with racy citrus acidity, making for the perfect aperitif or a great bottle for brunch.

To ease in to Jura whites, it's best to start with a good old-fashioned actual white wine, before moving on to those zany orange ones. Michel Gahier's 2009 Chardonnay 'La Fauquette' is a lovely example, brimming with Chablis-like minerality with undertones of dried apricot. Faint nutty aromas hint at the slightest bit of oxidation.

For an introduction to Vin Jaune, look no further than Jacques Puffeney's 2006 Arbois Vin Jaune. Monsieur Puffeney, known to his peers and admirers as "the Pope of Arbois," is one of the most well-known and revered vignerons in the region, and for good reason. This orange wine is produced only from the finest barrels after eight and a half years of aging under voile--two years longer than the minimum requirement. This enticing wine shows intense oxidation, dripping with honey, almond, and hazelnut aromas, dried apple flavors on the rich and creamy palate, and a surprisingly bone-dry finish.

It's not just the whites of Jura that are worth talking about--the reds are pretty fascinating themselves. Often receiving less attention and shorter aging from their white counterparts, Jura reds (made from Poulsard, Trousseau, and Pinot Noir) differ wildly from what most American palates are accustomed to consuming, in that they are so light as to frequently be mistaken for rosés, yet highly complex on the nose and palate, filled with floral and peppery aromas and often a healthy dose of terroir--or less euphemistically, funk.

Trousseau, the most powerful of the Jura red grapes, is often used to add structure and color in a blend alongside Poulsard--but it can undoubtedly shine on its own as well. Michel Gahier's 2012 Trousseau 'Les Grands Vergers' demonstrates intense, hearty blackcurrant fruit, cherry candy, earthy, smoked tea, and marked peppery and gamey notes, softened by hints of violet perfume.

Another bottling from Michel Gahier, 2012 Ploussard (a confusingly similar synonym of Poulsard) is much paler in color than the Trousseau, but is by no means lacking in flavor. The nose is lovely and floral, reminiscent of roses and ripe, juicy strawberries and cherries. The palate, however, is no delicate flower. Tannin and minerality give great structure to this faintly tinted wine, making it a "serious" wine that also happens to be very, very easy to drink. Another wonderful example isJacques Puffeney's 2011 Poulsard, which echoes many of the flavors in Mr. Gahier's bottling, which may have something to do with the fact that they are neighbors. The Gahier leans a bit towards a more fruit-forward style, with the Puffeney shows a little more earthiness.

All of these Jura wines (and many more!) are now available on our shelves. Whether you are just beginning to explore this intriguing appellation, or have been drinking Jura wines since before they were cool, there's definitely something for everyone in this un-sung, under-appreciated, and frequently under-valued region.

For an introduction to Vin Jaune, look no further than Jacques Puffeney's 2006 Arbois Vin Jaune. Monsieur Puffeney, known to his peers and admirers as "the Pope of Arbois," is one of the most well-known and revered vignerons in the region, and for good reason. This orange wine is produced only from the finest barrels after eight and a half years of aging under voile--two years longer than the minimum requirement. This enticing wine shows intense oxidation, dripping with honey, almond, and hazelnut aromas, dried apple flavors on the rich and creamy palate, and a surprisingly bone-dry finish.

It's not just the whites of Jura that are worth talking about--the reds are pretty fascinating themselves. Often receiving less attention and shorter aging from their white counterparts, Jura reds (made from Poulsard, Trousseau, and Pinot Noir) differ wildly from what most American palates are accustomed to consuming, in that they are so light as to frequently be mistaken for rosés, yet highly complex on the nose and palate, filled with floral and peppery aromas and often a healthy dose of terroir--or less euphemistically, funk.

Trousseau, the most powerful of the Jura red grapes, is often used to add structure and color in a blend alongside Poulsard--but it can undoubtedly shine on its own as well. Michel Gahier's 2012 Trousseau 'Les Grands Vergers' demonstrates intense, hearty blackcurrant fruit, cherry candy, earthy, smoked tea, and marked peppery and gamey notes, softened by hints of violet perfume.

Another bottling from Michel Gahier, 2012 Ploussard (a confusingly similar synonym of Poulsard) is much paler in color than the Trousseau, but is by no means lacking in flavor. The nose is lovely and floral, reminiscent of roses and ripe, juicy strawberries and cherries. The palate, however, is no delicate flower. Tannin and minerality give great structure to this faintly tinted wine, making it a "serious" wine that also happens to be very, very easy to drink. Another wonderful example isJacques Puffeney's 2011 Poulsard, which echoes many of the flavors in Mr. Gahier's bottling, which may have something to do with the fact that they are neighbors. The Gahier leans a bit towards a more fruit-forward style, with the Puffeney shows a little more earthiness.

All of these Jura wines (and many more!) are now available on our shelves. Whether you are just beginning to explore this intriguing appellation, or have been drinking Jura wines since before they were cool, there's definitely something for everyone in this un-sung, under-appreciated, and frequently under-valued region.

Labels:

Cremant Du Jura,

Domaine De Montbourgeau,

France,

French Wine,

Jacques Puffeney,

Jura,

Jura Wine,

Michel Gahier,

Orange Wine,

Paul Marcus Wines,

Ploussard,

Poulsard,

Savignin,

Trousseau,

Vin Jaune,

Wine

Friday, July 5, 2013

Only Excellent: The Story of the Wines of the Finger Lakes

|

Dr. Konstantin Frank

|

"Only Excellent. Good wine is not good enough for humans - only excellent will do."--Dr. Konstantin Frank

Once upon a time, the wines of the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York were little more than boozy grape juice, and those who produced them had resigned themselves to mediocrity. Believing that it was simply too cold in the region to grow quality, vitis vinifera grapes, winemakers of the region had long relied on the simple, sugary wines made from cold-hardy native American and French hybrid grapes like Concord and Catawba. It would take the persistence and dedication of a maverick mad scientist to turn the Finger Lakes into the impressive wine-producing region it is today.

Once upon a time, the wines of the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York were little more than boozy grape juice, and those who produced them had resigned themselves to mediocrity. Believing that it was simply too cold in the region to grow quality, vitis vinifera grapes, winemakers of the region had long relied on the simple, sugary wines made from cold-hardy native American and French hybrid grapes like Concord and Catawba. It would take the persistence and dedication of a maverick mad scientist to turn the Finger Lakes into the impressive wine-producing region it is today.

In 1951, the prayers of those who desired great wine were answered with the arrival of Dr. Konstantin Frank, a 54-year-old Ukrainian immigrant, to the region. Although in the old country Dr. Frank had been a respected viticulturist, English was not one of the nine languages he spoke, so in New York he was forced to take a low-level, menial labor job at the Geneva Research Station, a grape research facility at Cornell University. Once he had found his in, Dr. Frank immediately began urging the local winemakers to experiment with planting vinifera grape varieties. He explained that his thesis at the Odessa Polytechnic Institute had been on techniques for growing vitis vinifera in a cold climate, and that if it could be done in the below-freezing winters of Ukraine, it could certainly be done in slightly milder New York.

|

Winter in the Finger Lakes

|

As most mad scientists are at first, Dr. Frank was ridiculed by the local winemaking community. His idea that the failure of vinifera wines in the region was due not to icy temperatures but to the lack of proper rootstock was viewed as ludicrous (although admittedly, he may have hurt his case by telling women who drank labrusca wines that they would be unable to get pregnant as a result). The ornery Ukrainian viticulturist, however, refused to give up. After much perseverance, he finally was able to convince local sparkling wine producer Charles Fournier to give him a chance. Together, they planted thousands of Chardonnay and Riesling vines grafted onto hardy rootstock in Quebec, Canada, and then waited patiently until 1957, when the vines proved Dr. Frank's hypothesis to be correct.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Frank founded Vinifera Wine Cellars, which will celebrate its 50th anniversary next month, in Hammondsport, New York. The first vintage, a trockenbeerenauslese Riesling, was released in 1962, and upon tasting the success for themselves, other winemakers sheepishly began to follow suit. The Finger Lakes region is now home to more than 100 wineries producing wines made from vinifera grapes, the best of which are often bone-dry, aromatic Rieslings, although great success has been had with Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, and Gewürztraminer as well. More recently, experimentation with Austrian varieties such as Blaufrankisch and Grüner Veltliner has led to pleasing results.

|

Keuka Lake in Autumn

|

In addition to Dr. Frank's Vinifera Wine Cellars, now run by Konstantin's grandson Frederick Frank and still producing some of the best wines in the state, top Finger Lakes producers include Sheldrake Point, Red Tail Ridge, Ravines, Hermann J. Wiemer, and Hearts & Hands. These wines are still sorely under-appreciated in the national marketplace, which makes them a little hard to find on the West Coast, but luckily more and more are finding their way here. The easiest to find include bottlings by Ravines, Red Tail Ridge, (particularly their earthy and unusual Lemberger (a synonym for Blaufrankisch), and of course, the descendants of Dr. Frank himself. If you haven't tried the wines of the Finger Lakes, you are missing out. But if you, like myself, have tried them and loved them, then you can thank Dr. Konstantin Frank.

Australia's Best Kept Secret: It's Not All Yellowtail and Foster's!

At most of the places where I have sold wine, I have frequently encountered guests visiting from Australia. As they scan the selection, they always ask the same question: "where are all of your Aussie wines?" After a recent visit to Melbourne and nearby wine region the Mornington Peninsula, I have come to realize that the answer is not what I previously thought it was.

For years, I have believed that Australian wines just didn't quite jive with my palate. Those I had tasted (mostly Shiraz) were generally over-extracted fruit bombs with too much oak and more residual sugar than I felt my beloved Syrah grape deserved to be laden with. But after having sampled a diverse array of Australian wines over the last few weeks, I now know the truth: there are fantastic wines being made in Australia, but those clever Aussies are keeping the good stuff for themselves!

Before heading to my first true Australian barbecue, I stopped at a nice little wine shop near my hotel to grab a bottle of something refreshing to help cool us off on a hot Melbourne summer day. Taking my time walking around the store, I observed a few things of note. One was that apart from a smattering of Italian and French wines, the vast majority of the selections were Australian, a stark contrast to most wine shops stateside. Very few of them were wines that I recognized, apart from the obligatory Penfolds, d'Arenberg, and yes, Yellowtail. Most of the bottlings had names and labels unfamiliar to me as an American. These were the boutique wines of Australia, the ones made in quantities too small for exporting. Another thing I noticed was that this particular wine shop only carried one American wine: Gallo White Zinfandel. That explains why the Aussies are about as excited about our wines as I had been about theirs! After a quick chat with the affable store manager, I left with a cold bottle of 2012 Pewsey Vale Riesling from the Eden Valley region.

At the barbecue, the wine turned out to be a huge hit--with me. After first tasting its bone-dry, mineral rich character with bright lemon-lime citrus exploding on the palate, I surrepititiously tucked the bottle behind a few others in the ice bucket, making sure never to stray so far as to let it out of my line of vision. No one else seemed to notice its presence, so I poured myself another glass, and then another. Soon, I had finished the entire bottle. The wine reminded me of some of my favorite Finger Lakes Rieslings, (I'm looking at you, Sheldrake Point 2007 Reserve Riesling!) and I was truly impressed. At that point, I became very excited to see what else this underrated wine-producing country had to offer.

The next day, on my way to another barbecue (it's true, the Aussies really do barbecue every day!), I picked up a bottle of 2012 Dominique Portet Fontaine Rosé, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Shiraz from the Yarra Valley, recommended by the same gentleman. I was skeptical of the blend, but the reliable pale salmon color told me this wine would not betray my taste buds--and it didn't. Crisp, clean and dry, its juicy red berry flavors with hints of fresh herbs made this wine the perfect quaffing beverage to cool off after a rousing family cricket match. Again, I may as well have just stuck a straw in the bottle, because I was fairly unwilling to share this extremely tasty wine.

At restaurants and bars, there were more delightful surprises to be found. At the Builders Arms Hotel, a glass of NV Bress sparkling wine (a mineral-rich blend of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay) from Macedon, Victoria made for a perfect midday refreshment while taking a break from exploring the city's eclectic Fitzroy neighborhood.

A block away, the Gertrude Street Enoteca, a combination bottle shop and wine bar, was a haven for those looking to explore Australia's diverse vinous offerings. I salivated for a while over the bottle selection, including a Lagrein from Macedon that I'll have to try on my next visit, and then sat down to taste a few of their by-the-glass offerings. The 2012 Cherubino 'Laissez Faire' Fiano, Western Australia's take on the classic white wine of Campania, Fiano di Avellino, paid a pleasing tribute to its southern Italian mentor, fresh and lively now, but sure to develop lovely honeyed and spicy notes with age. But the true star of the show was the 2009 Avani Syrah. Yes, you read that correctly. A burgeoning trend among Australian winemakers is to eschew the nation's famous 'Shiraz' nickname in favor of lighter-handed, minimal-intervention, lower-alcohol, northern-Rhône-style wines labeled with the grape's French name: Syrah (the two grapes are one and the same!). This Mornington Peninsula wine, which clocks in at just under 13.5% alcohol (the 2011 vintage is under 12%!) is the first vintage produced by Shashi Singh, an Indian-born chemist-turned-restaurateur-turned-oenologist who moved to Melbourne with her chef husband thirty years ago. She applies biodynamic processes in the vineyard with the result of a beautiful, aromatic wine with notes of pepper, brooding black fruit, earth, and a hint of violet.

A block away, the Gertrude Street Enoteca, a combination bottle shop and wine bar, was a haven for those looking to explore Australia's diverse vinous offerings. I salivated for a while over the bottle selection, including a Lagrein from Macedon that I'll have to try on my next visit, and then sat down to taste a few of their by-the-glass offerings. The 2012 Cherubino 'Laissez Faire' Fiano, Western Australia's take on the classic white wine of Campania, Fiano di Avellino, paid a pleasing tribute to its southern Italian mentor, fresh and lively now, but sure to develop lovely honeyed and spicy notes with age. But the true star of the show was the 2009 Avani Syrah. Yes, you read that correctly. A burgeoning trend among Australian winemakers is to eschew the nation's famous 'Shiraz' nickname in favor of lighter-handed, minimal-intervention, lower-alcohol, northern-Rhône-style wines labeled with the grape's French name: Syrah (the two grapes are one and the same!). This Mornington Peninsula wine, which clocks in at just under 13.5% alcohol (the 2011 vintage is under 12%!) is the first vintage produced by Shashi Singh, an Indian-born chemist-turned-restaurateur-turned-oenologist who moved to Melbourne with her chef husband thirty years ago. She applies biodynamic processes in the vineyard with the result of a beautiful, aromatic wine with notes of pepper, brooding black fruit, earth, and a hint of violet.

After getting a nice base of beer in our stomachs to begin our day of wine tasting, we moved on to scenic Tuck's Ridge, where the quality of the wine matched the friendliness of the tasting room staff. It was here that I realized that the Mornington Peninsula resembles the Anderson Valley in more than just aesthetics. A coastal influence and significant diurnal swing (warm days followed by cool nights) help to produce crisp, acidic whites and light, earthy reds. Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Rosé, and Pinot Noir were the standouts, but the bottle I chose to bring home was a 2012 Savignin, a grape most commonly grown in the Jura region of France, which I learned had until as recently as 2008 been mistaken in Australia for the Spanish grape Albariño.

For years, I have believed that Australian wines just didn't quite jive with my palate. Those I had tasted (mostly Shiraz) were generally over-extracted fruit bombs with too much oak and more residual sugar than I felt my beloved Syrah grape deserved to be laden with. But after having sampled a diverse array of Australian wines over the last few weeks, I now know the truth: there are fantastic wines being made in Australia, but those clever Aussies are keeping the good stuff for themselves!

Before heading to my first true Australian barbecue, I stopped at a nice little wine shop near my hotel to grab a bottle of something refreshing to help cool us off on a hot Melbourne summer day. Taking my time walking around the store, I observed a few things of note. One was that apart from a smattering of Italian and French wines, the vast majority of the selections were Australian, a stark contrast to most wine shops stateside. Very few of them were wines that I recognized, apart from the obligatory Penfolds, d'Arenberg, and yes, Yellowtail. Most of the bottlings had names and labels unfamiliar to me as an American. These were the boutique wines of Australia, the ones made in quantities too small for exporting. Another thing I noticed was that this particular wine shop only carried one American wine: Gallo White Zinfandel. That explains why the Aussies are about as excited about our wines as I had been about theirs! After a quick chat with the affable store manager, I left with a cold bottle of 2012 Pewsey Vale Riesling from the Eden Valley region.

At the barbecue, the wine turned out to be a huge hit--with me. After first tasting its bone-dry, mineral rich character with bright lemon-lime citrus exploding on the palate, I surrepititiously tucked the bottle behind a few others in the ice bucket, making sure never to stray so far as to let it out of my line of vision. No one else seemed to notice its presence, so I poured myself another glass, and then another. Soon, I had finished the entire bottle. The wine reminded me of some of my favorite Finger Lakes Rieslings, (I'm looking at you, Sheldrake Point 2007 Reserve Riesling!) and I was truly impressed. At that point, I became very excited to see what else this underrated wine-producing country had to offer.

The next day, on my way to another barbecue (it's true, the Aussies really do barbecue every day!), I picked up a bottle of 2012 Dominique Portet Fontaine Rosé, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Shiraz from the Yarra Valley, recommended by the same gentleman. I was skeptical of the blend, but the reliable pale salmon color told me this wine would not betray my taste buds--and it didn't. Crisp, clean and dry, its juicy red berry flavors with hints of fresh herbs made this wine the perfect quaffing beverage to cool off after a rousing family cricket match. Again, I may as well have just stuck a straw in the bottle, because I was fairly unwilling to share this extremely tasty wine.

.JPG) |

| After discovering my natural talent for cricket, a nice, cold glass of rosé was necessary. |

A block away, the Gertrude Street Enoteca, a combination bottle shop and wine bar, was a haven for those looking to explore Australia's diverse vinous offerings. I salivated for a while over the bottle selection, including a Lagrein from Macedon that I'll have to try on my next visit, and then sat down to taste a few of their by-the-glass offerings. The 2012 Cherubino 'Laissez Faire' Fiano, Western Australia's take on the classic white wine of Campania, Fiano di Avellino, paid a pleasing tribute to its southern Italian mentor, fresh and lively now, but sure to develop lovely honeyed and spicy notes with age. But the true star of the show was the 2009 Avani Syrah. Yes, you read that correctly. A burgeoning trend among Australian winemakers is to eschew the nation's famous 'Shiraz' nickname in favor of lighter-handed, minimal-intervention, lower-alcohol, northern-Rhône-style wines labeled with the grape's French name: Syrah (the two grapes are one and the same!). This Mornington Peninsula wine, which clocks in at just under 13.5% alcohol (the 2011 vintage is under 12%!) is the first vintage produced by Shashi Singh, an Indian-born chemist-turned-restaurateur-turned-oenologist who moved to Melbourne with her chef husband thirty years ago. She applies biodynamic processes in the vineyard with the result of a beautiful, aromatic wine with notes of pepper, brooding black fruit, earth, and a hint of violet.

A block away, the Gertrude Street Enoteca, a combination bottle shop and wine bar, was a haven for those looking to explore Australia's diverse vinous offerings. I salivated for a while over the bottle selection, including a Lagrein from Macedon that I'll have to try on my next visit, and then sat down to taste a few of their by-the-glass offerings. The 2012 Cherubino 'Laissez Faire' Fiano, Western Australia's take on the classic white wine of Campania, Fiano di Avellino, paid a pleasing tribute to its southern Italian mentor, fresh and lively now, but sure to develop lovely honeyed and spicy notes with age. But the true star of the show was the 2009 Avani Syrah. Yes, you read that correctly. A burgeoning trend among Australian winemakers is to eschew the nation's famous 'Shiraz' nickname in favor of lighter-handed, minimal-intervention, lower-alcohol, northern-Rhône-style wines labeled with the grape's French name: Syrah (the two grapes are one and the same!). This Mornington Peninsula wine, which clocks in at just under 13.5% alcohol (the 2011 vintage is under 12%!) is the first vintage produced by Shashi Singh, an Indian-born chemist-turned-restaurateur-turned-oenologist who moved to Melbourne with her chef husband thirty years ago. She applies biodynamic processes in the vineyard with the result of a beautiful, aromatic wine with notes of pepper, brooding black fruit, earth, and a hint of violet.

At the Enoteca, I met second-generation winemaker Andrew Marks, who has made wine all over the world but calls the Yarra Valley home. He spoke with me about the aforementioned Syrah trend, as well as the movement of many winemakers toward lower-alcohol, terroir-expressive wines like Shashi's. I told him of my plans to go wine tasting the following day, and if the Avani Syrah hadn't already convinced me to head to the Mornington Peninsula, Andrew sealed the deal.

|

| Any day that starts with a paddle of beer is bound to be a good day. |

.JPG) |

| Hops grown on site |

The next morning, the adventure began...at a brewery. Red Hill Brewery, to be exact. If the Mornington Peninsula didn't remind me enough of driving through Mendocino's Anderson Valley, the taco truck parked right outside the brewery made me feel right at home. A paddle of beer was deemed the most appropriate way to start the day, which included samples of Red Hill's Golden Ale, Wheat Beer, Black Rye IPA, and Irish Red Ale. All were thoroughly enjoyable, and I learned that Australia is a true contender on the microbrewery scene. It should be noted that I did not see a single bottle of Foster's the entire time I was in the country, and am now thoroughly convinced that "Foster's" is Australian for "gullible Americans."

.JPG) |

| Red Hill Brewery |

After getting a nice base of beer in our stomachs to begin our day of wine tasting, we moved on to scenic Tuck's Ridge, where the quality of the wine matched the friendliness of the tasting room staff. It was here that I realized that the Mornington Peninsula resembles the Anderson Valley in more than just aesthetics. A coastal influence and significant diurnal swing (warm days followed by cool nights) help to produce crisp, acidic whites and light, earthy reds. Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Rosé, and Pinot Noir were the standouts, but the bottle I chose to bring home was a 2012 Savignin, a grape most commonly grown in the Jura region of France, which I learned had until as recently as 2008 been mistaken in Australia for the Spanish grape Albariño.

|

| The line-up at Tuck's Ridge |

This wine was not available for tasting due to its extremely limited production, but it promises to excite my salivary glands with white peach, citrus pith, and apricots on the nose and palate--an experience I am quite looking forward to.

|

| Tuck's Ridge vineyards |

The next stop was Main Ridge Estate, where the specialties were Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. The group favorite, however, turned out to be a 2010 Merlot, whose soft tannins and dark fruit aromas enticed me in a way Merlot often fails to achieve. Flipping through a guide to Victoria's wineries that I found at Main Ridge, I perked up when I noticed that a few wineries were producing wines from one of my favorite underrated grapes, Gamay.

|

| Eldridge Estate |

I asked where to find the best Gamay and was instructed to visit Eldridge Estate. I quickly found that I had not been led astray. This intensely aromatic wine had all of the best qualities of a Cru Beaujolais, and the winery's other offerings, particularly their two Pinot Noirs, were excellent as well.

All good things must come to an end, and our little group decided to finish the day the same way we started--at a brewery (this is what happens when you go wine tasting with beer drinkers). We found ourselves atMornington Brewery, washing down more entire pizzas than I'd like to admit with delicious English-

style Brown Ale.

Needless to say, I was very pleasantly surprised by both the wine and the beer in the land down under. I boarded my plane home with a mixture of melancholy and excitement--sad that I had to leave this wonderful country and all of the delicious things it had to offer, but looking forward to coming back to The Barrel Room and sharing my discovery with my colleagues and our guests. Luckily, soon after my return I had the opportunity to attend a trade tasting of Australian wines, where I was able to sample some fantastic bottlings that actually are available in California. I was thrilled to taste such wines as BK Wines Cult Syrah from McLaren Vale, South Australia, Dandelion Wines Eden Valley Riesling, and the entire lineup from Fowles Wine--run by lovely husband-and-wife team Matt and Lu Fowles, who assure me that their 'Ladies Who Shoot Their Lunch' Shiraz would pair fantastically with 'roo, my new favorite meat.

|

| My first bite of 'roo. Once you go marsupial, you never go back. |

The Dry Wine Dilemma: Clearing up Confusion

Some wine terms sound completely ridiculous. Just the other day, I caught myself describing a 1985 Bordeaux as being "not so much fruitier as it is brighter" than the '95 I had tasted a day earlier. I realized as soon as the words came out of my mouth that I sounded like Paul Giamatti's character in the movie 'Sideways.' Even worse was that my tasting companions, both seasoned wine drinkers like myself, nodded in agreement. I was appalled--I would have preferred if they had made fun of me for sounding like a snob!

But the fact of the matter is that certain 'ridiculous'-sounding terms can be very useful and important in describing wine--but perhaps not in the way that you might think. Sure, we winos enjoy sniffing and swirling together and comparing notes, in the way that sports fans might enjoy talking about a great football play that they just watched or fashion-lovers may discuss the latest Zac Posen runway show.

People often tell me apologetically that they are not very good at describing wine. In such instances, I share with them my belief that it is not their duty to excel in this activity; that's my job (and my hobby--we wine people are nerds). You'll certainly never find me apologizing to a surgeon for not being able to perform a heart transplant, or to an accountant for not being able to fill out complicated tax forms. I do believe, however, that there is one important exception to this rule. I think that anyone who enjoys drinking wine and does so on at least a semi-regular basis should know a few basic terms to describe what they like to drink. That way, the person whose job it actually is to understand the terminology and apply it to the wine list in question can be of optimal assistance in finding a glass or bottle of wine that the customer will enjoy.

Unfortunately, there is a big problem with one of the most important of these terms: 'dry.' It seems so straightforward, doesn't it? If you take it literally (and without proper instruction, why wouldn't you?), it seems to imply that drying feeling you get in your mouth after taking a sip of an intense red wine, like a Nebbiolo from Piedmont or a young Bordeaux. But no--that feeling has its own, far less obvious term: 'tannic.' Tannin, existing in the skins of red wine grapes, is what gives you the sensation that you just licked a flannel shirt. In more extreme cases, it may temporarily deprive you of the ability to separate your gums from the inside of your lip. Many people understandably mistake tannin for dryness when describing wine.

Unless you're a wine geek like me, you very well may now be wondering, "well then what is a dry wine?" The answer is definitely not intuitive, but it is simple. In the world of wine, dry is merely the opposite of sweet. Of course, we could get complicated and talk about wines that are 'off-dry' or 'semi-dry,' but that just means that they are a little bit sweet. The problem lies in the divide in understanding between the experienced winos of the world and the casual wine drinker who has never taken a formal course in wine tasting. This breakdown in communication can lead to disastrous wine selection results!

I once served a woman who was unfamiliar with many of the selections available on the wine list asked for guidance in choosing a glass. I asked her what she liked to drink and she confidently answered that she enjoyed red wines that were both dry and earthy. "Easy enough," I thought. Most earthy wines are quite dry (as in, little or no residual sugar is left after fermentation) so I assumed it would not be difficult to help her pick out her ideal beverage. I poured her a few tastes, waiting expectantly as she sipped. I was surprised when she asked if I had anything drier--it doesn't get any drier than this!

A lightbulb went off over my head and I asked her, cautiously, "what is it exactly that you mean when you say the word 'dry'?" Quickly, she answered, "you know, that feeling you get in your mouth after you take a sip when it feels really dry!" I instantly realized she was referring to tannin, and explained the confusion of the two terms. She then wrote down in her notebook for future reference that she likes "earthy, tannic wines." She ended up being quite happy with a 2004 Nebbiolo that scored high marks for her in both categories.

So why would such a simple and important word have such a counterintuitive definition? The answer is not quite clear. A search for the term's etymology leads simply to speculation and dead ends. Charles Hodgson's book History of Wine Words skips the subject altogether, leaving a gaping, confusing hole between 'drink' and 'Dry Creek Valley.' A prevailing theory is that the idea that sugar was once thought to 'evaporate' like water during fermentation, until it could be presumed 'dry;' another one relates to wine storage technology (or lack thereof) during medieval times, which led to a tradeoff between sweetness and astringency, so that non-sweet wines would have been more astringent (as in 'tannic' or 'dry') on the palate, and sweet wines less so.

Unfortunately, it's difficult to imagine a solution to this semantic mix-up. We can only continue the crusade to educate wine drinkers on this peculiarity for which we can probably blame the French, who first used the term vin sec (dry wine) in print around the year 1200 (although it's hard to stay mad at them when they make such delicious wine!) On the other side of the coin, I believe it is very important for bartenders, sommeliers, and restaurant servers to be cognizant and understanding of this issue. When you deal with wine day in and day out and are constantly surrounded by people who do the same, it is easy to forget that not everyone has the same knowledge of the subject. We can do our part by always remembering to ask, "what exactly is it that you mean when you say the word 'dry'?"

People often tell me apologetically that they are not very good at describing wine. In such instances, I share with them my belief that it is not their duty to excel in this activity; that's my job (and my hobby--we wine people are nerds). You'll certainly never find me apologizing to a surgeon for not being able to perform a heart transplant, or to an accountant for not being able to fill out complicated tax forms. I do believe, however, that there is one important exception to this rule. I think that anyone who enjoys drinking wine and does so on at least a semi-regular basis should know a few basic terms to describe what they like to drink. That way, the person whose job it actually is to understand the terminology and apply it to the wine list in question can be of optimal assistance in finding a glass or bottle of wine that the customer will enjoy.

Unfortunately, there is a big problem with one of the most important of these terms: 'dry.' It seems so straightforward, doesn't it? If you take it literally (and without proper instruction, why wouldn't you?), it seems to imply that drying feeling you get in your mouth after taking a sip of an intense red wine, like a Nebbiolo from Piedmont or a young Bordeaux. But no--that feeling has its own, far less obvious term: 'tannic.' Tannin, existing in the skins of red wine grapes, is what gives you the sensation that you just licked a flannel shirt. In more extreme cases, it may temporarily deprive you of the ability to separate your gums from the inside of your lip. Many people understandably mistake tannin for dryness when describing wine.

Unless you're a wine geek like me, you very well may now be wondering, "well then what is a dry wine?" The answer is definitely not intuitive, but it is simple. In the world of wine, dry is merely the opposite of sweet. Of course, we could get complicated and talk about wines that are 'off-dry' or 'semi-dry,' but that just means that they are a little bit sweet. The problem lies in the divide in understanding between the experienced winos of the world and the casual wine drinker who has never taken a formal course in wine tasting. This breakdown in communication can lead to disastrous wine selection results!

I once served a woman who was unfamiliar with many of the selections available on the wine list asked for guidance in choosing a glass. I asked her what she liked to drink and she confidently answered that she enjoyed red wines that were both dry and earthy. "Easy enough," I thought. Most earthy wines are quite dry (as in, little or no residual sugar is left after fermentation) so I assumed it would not be difficult to help her pick out her ideal beverage. I poured her a few tastes, waiting expectantly as she sipped. I was surprised when she asked if I had anything drier--it doesn't get any drier than this!

A lightbulb went off over my head and I asked her, cautiously, "what is it exactly that you mean when you say the word 'dry'?" Quickly, she answered, "you know, that feeling you get in your mouth after you take a sip when it feels really dry!" I instantly realized she was referring to tannin, and explained the confusion of the two terms. She then wrote down in her notebook for future reference that she likes "earthy, tannic wines." She ended up being quite happy with a 2004 Nebbiolo that scored high marks for her in both categories.

So why would such a simple and important word have such a counterintuitive definition? The answer is not quite clear. A search for the term's etymology leads simply to speculation and dead ends. Charles Hodgson's book History of Wine Words skips the subject altogether, leaving a gaping, confusing hole between 'drink' and 'Dry Creek Valley.' A prevailing theory is that the idea that sugar was once thought to 'evaporate' like water during fermentation, until it could be presumed 'dry;' another one relates to wine storage technology (or lack thereof) during medieval times, which led to a tradeoff between sweetness and astringency, so that non-sweet wines would have been more astringent (as in 'tannic' or 'dry') on the palate, and sweet wines less so.

Unfortunately, it's difficult to imagine a solution to this semantic mix-up. We can only continue the crusade to educate wine drinkers on this peculiarity for which we can probably blame the French, who first used the term vin sec (dry wine) in print around the year 1200 (although it's hard to stay mad at them when they make such delicious wine!) On the other side of the coin, I believe it is very important for bartenders, sommeliers, and restaurant servers to be cognizant and understanding of this issue. When you deal with wine day in and day out and are constantly surrounded by people who do the same, it is easy to forget that not everyone has the same knowledge of the subject. We can do our part by always remembering to ask, "what exactly is it that you mean when you say the word 'dry'?"

How do they Get the Blueberries into the Wine?: A Primer on Wine Aromas

|

| Wine tasting is very serious business |

"It smells fruity," one of them said.

"Yes," replied her friend, "sort of like blueberries!"

"Exactly," I responded. "Blueberry is a very common aroma in Petite Sirah."

The women smiled with satisfaction, pondering the wine as they sniffed and sipped. But then the first woman's face contorted in confusion. "Wait a second..." she began, "how do they get the blueberries into the wine?!"

To the novice wine drinker, this can be an extremely confusing concept. Sometimes a wine has such a pronounced smell of blueberries, or of roses, or of ripe fresh peaches, that it seems impossible that the scent could have been achieved in any other manner than by tossing a bag of groceries in with the fermenting grapes. But unless you are making blueberry wine, peach wine, or rose wine (all of which do exist), the only fruit that will ever see the inside of the oak barrel or stainless steel fermenting tank is in fact, the grape.

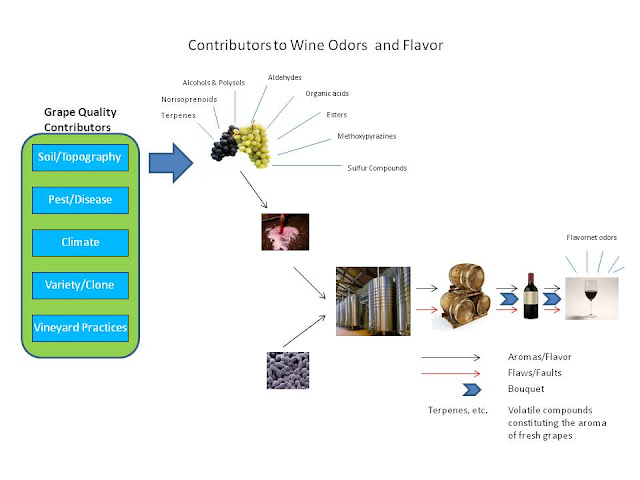

So how do wines made from little more than fermented grapes and yeast end up smelling like, well, anything but? And what makes each wine different? There are a number of factors that contribute to the aroma (or the bouquet--more on that later) of a wine.

One of the most important determinants of a wine's aroma is the type of grape(s) from which it is made. Each grape contains tiny amounts of aromatic and phenolic compounds--chemical compounds with very unromantic names like methoxypyrazine, which gives Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc their characteristic grassy aromas, or zingerone, the vaguely onomatopoeic moniker for the compound responsible for spiciness (zing!) in Syrah. Monoterpenes, a class of compounds including linalool and geraniol, lend a floral quality to Gewürztraminer, Muscat, and Riesling. If you were to pick a ripe grape off of the vine and eat it, you may have a hard time perceiving any of these chemical compounds. Fermentation, however, has a magnifying effect on their aromas, and they are often clearly perceptible in the finished product.

Then there is the "bouquet"--a somewhat controversial and mostly unnecessary term that, depending on who you ask, either means the aromas that come from the winemaking process or the aromas that come from aging. Between you and me, I'm fine with calling them all aromas. Or scents. Or smells. Whatever works for you. But although the term doesn't matter, these two processes have an undeniable effect on the way a wine smells. A winemaker can choose to age a wine in stainless steel barrels, preserving the purity of the fruit aromas, or in oak barrels, which (depending on their age and region of origin) can impart hints of toast, cedar, vanilla, or coconut. The decision to allow a white wine such as Chardonnay to undergo malolactic fermentation can result in a scent not unlike buttered popcorn, due to the conversion of crisp, tart malic acid (think green apples) to soft lactic acid (think yogurt). Allowing a wine to sit with the dead yeast cells (lees) following fermentation will lead to a yeasty, brioche-like smell. An aging wine will see its fresh fruit aromas turn to those of dried, cooked, or baked fruit, while other earthy, floral, mineral, or even animal aromas develop as well. The scent of the wine will become much more layered and complex as it matures, although if you let it mature for too long, its aroma will turn to that of a nice vinegar for cooking.

|

| Oak barrel aging can lead to toasty, woody, and vanilla flavors in the finished wine |

Of course, despite the fact that there is some science behind all this, that doesn't mean everyone is going to perceive the same thing all of the time, or even half of the time. Everyone's nose and palate is different, and we all have different thresholds of perception. Personally, I can almost never detect the smell of mint in a wine until someone else points it out, but I am always among the first to pick up on the smell of plum. Some people can instantly discern that a wine that has been ever-so-slightly damaged by cork taint, while others may happily gulp down the entire bottle without batting an eye. This doesn't mean anyone is "wrong," any more than one would be "wrong" for preferring vanilla ice cream to chocolate.

|

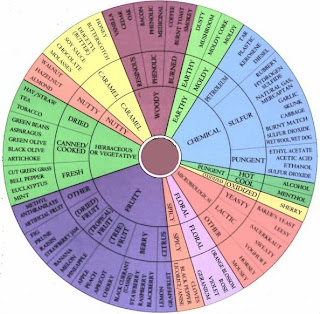

| the aroma wheel |

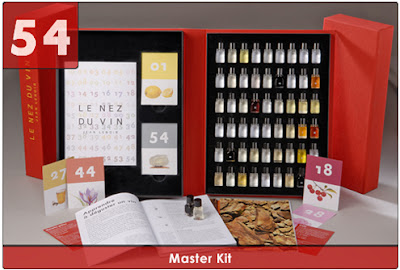

If you want to get better at this wine-sniffing thing, you have options. A very useful tool is the aroma wheel, the creation of Ann C. Noble, a sensory chemist and former U.C. Davis professor. You can buy one for $6, and use it to identify scents by narrowing them down from the general (fruity) to the sort-of-general (berry) to the specific (strawberry), helping to make the process a little less daunting. Another suggestion, courtesy of my former Intro to Wines professor, is to learn what things smell like. It's pretty simple. Go to the farmers' market or a spice shop, pick things up, and sniff them. Commit their scents to memory. If you don't know what gooseberries smell like, find some gooseberries in the produce aisle and take a big whiff. Of course, if anyone sees you do this, you might have to buy them. Or, if you have lots of money and cannot figure out what to do with it, spend some of it on an aroma kit like Le Nez du Vin, which basically lets you do all of that without the awkward trip to the grocery store.

|

| Le Nez du Vin aroma kit |

At the end of the day, the most important thing to do while drinking a wine is to enjoy it, not to try to think of obtuse flowery descriptions (unless, of course, you are a wine reviewer). But identifying aromatic characteristics can be fun, especially with a group of friends. And the more you drink, the more creative your descriptions will become (some excerpts from my tasting group's late-night notes: 'kinda like a burrito,' 'Aunt Jemima maple syrup,' 'third grade snack time with apple juice and graham crackers' and 'Pert Plus shampoo - green apple scent.' Don't take yourself too seriously. And remember, practice makes perfect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)