|

| Wine tasting is very serious business |

"It smells fruity," one of them said.

"Yes," replied her friend, "sort of like blueberries!"

"Exactly," I responded. "Blueberry is a very common aroma in Petite Sirah."

The women smiled with satisfaction, pondering the wine as they sniffed and sipped. But then the first woman's face contorted in confusion. "Wait a second..." she began, "how do they get the blueberries into the wine?!"

To the novice wine drinker, this can be an extremely confusing concept. Sometimes a wine has such a pronounced smell of blueberries, or of roses, or of ripe fresh peaches, that it seems impossible that the scent could have been achieved in any other manner than by tossing a bag of groceries in with the fermenting grapes. But unless you are making blueberry wine, peach wine, or rose wine (all of which do exist), the only fruit that will ever see the inside of the oak barrel or stainless steel fermenting tank is in fact, the grape.

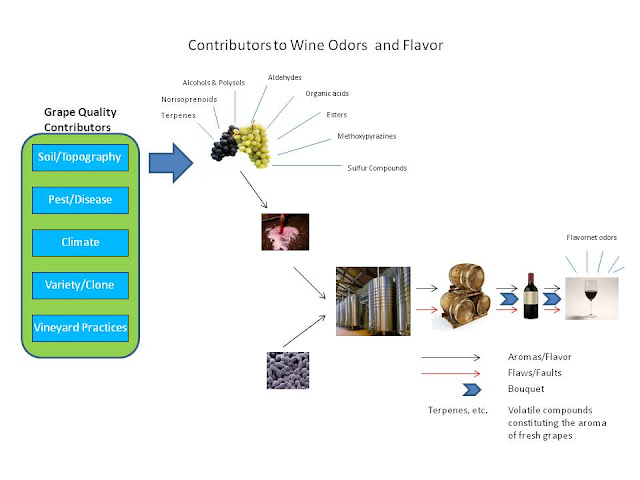

So how do wines made from little more than fermented grapes and yeast end up smelling like, well, anything but? And what makes each wine different? There are a number of factors that contribute to the aroma (or the bouquet--more on that later) of a wine.

One of the most important determinants of a wine's aroma is the type of grape(s) from which it is made. Each grape contains tiny amounts of aromatic and phenolic compounds--chemical compounds with very unromantic names like methoxypyrazine, which gives Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc their characteristic grassy aromas, or zingerone, the vaguely onomatopoeic moniker for the compound responsible for spiciness (zing!) in Syrah. Monoterpenes, a class of compounds including linalool and geraniol, lend a floral quality to Gewürztraminer, Muscat, and Riesling. If you were to pick a ripe grape off of the vine and eat it, you may have a hard time perceiving any of these chemical compounds. Fermentation, however, has a magnifying effect on their aromas, and they are often clearly perceptible in the finished product.

Then there is the "bouquet"--a somewhat controversial and mostly unnecessary term that, depending on who you ask, either means the aromas that come from the winemaking process or the aromas that come from aging. Between you and me, I'm fine with calling them all aromas. Or scents. Or smells. Whatever works for you. But although the term doesn't matter, these two processes have an undeniable effect on the way a wine smells. A winemaker can choose to age a wine in stainless steel barrels, preserving the purity of the fruit aromas, or in oak barrels, which (depending on their age and region of origin) can impart hints of toast, cedar, vanilla, or coconut. The decision to allow a white wine such as Chardonnay to undergo malolactic fermentation can result in a scent not unlike buttered popcorn, due to the conversion of crisp, tart malic acid (think green apples) to soft lactic acid (think yogurt). Allowing a wine to sit with the dead yeast cells (lees) following fermentation will lead to a yeasty, brioche-like smell. An aging wine will see its fresh fruit aromas turn to those of dried, cooked, or baked fruit, while other earthy, floral, mineral, or even animal aromas develop as well. The scent of the wine will become much more layered and complex as it matures, although if you let it mature for too long, its aroma will turn to that of a nice vinegar for cooking.

|

| Oak barrel aging can lead to toasty, woody, and vanilla flavors in the finished wine |

Of course, despite the fact that there is some science behind all this, that doesn't mean everyone is going to perceive the same thing all of the time, or even half of the time. Everyone's nose and palate is different, and we all have different thresholds of perception. Personally, I can almost never detect the smell of mint in a wine until someone else points it out, but I am always among the first to pick up on the smell of plum. Some people can instantly discern that a wine that has been ever-so-slightly damaged by cork taint, while others may happily gulp down the entire bottle without batting an eye. This doesn't mean anyone is "wrong," any more than one would be "wrong" for preferring vanilla ice cream to chocolate.

|

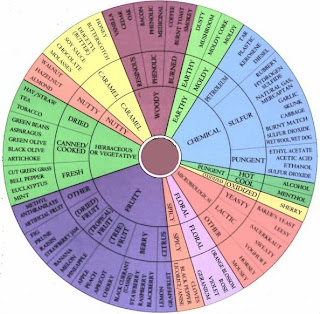

| the aroma wheel |

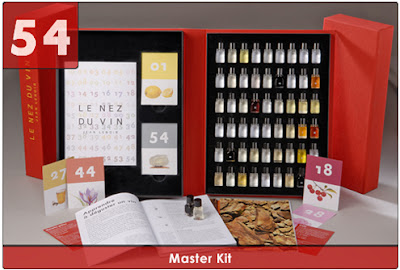

If you want to get better at this wine-sniffing thing, you have options. A very useful tool is the aroma wheel, the creation of Ann C. Noble, a sensory chemist and former U.C. Davis professor. You can buy one for $6, and use it to identify scents by narrowing them down from the general (fruity) to the sort-of-general (berry) to the specific (strawberry), helping to make the process a little less daunting. Another suggestion, courtesy of my former Intro to Wines professor, is to learn what things smell like. It's pretty simple. Go to the farmers' market or a spice shop, pick things up, and sniff them. Commit their scents to memory. If you don't know what gooseberries smell like, find some gooseberries in the produce aisle and take a big whiff. Of course, if anyone sees you do this, you might have to buy them. Or, if you have lots of money and cannot figure out what to do with it, spend some of it on an aroma kit like Le Nez du Vin, which basically lets you do all of that without the awkward trip to the grocery store.

|

| Le Nez du Vin aroma kit |

At the end of the day, the most important thing to do while drinking a wine is to enjoy it, not to try to think of obtuse flowery descriptions (unless, of course, you are a wine reviewer). But identifying aromatic characteristics can be fun, especially with a group of friends. And the more you drink, the more creative your descriptions will become (some excerpts from my tasting group's late-night notes: 'kinda like a burrito,' 'Aunt Jemima maple syrup,' 'third grade snack time with apple juice and graham crackers' and 'Pert Plus shampoo - green apple scent.' Don't take yourself too seriously. And remember, practice makes perfect.

No comments:

Post a Comment